Giving thanks for this life

Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.

- Henry David Thoreau

To your tired eyes I bring a vision

Of a different world,

So new and clean and fresh

You will forget the pain and sorrow

that you saw before.

Yet this a vision is

Which you must share

With everyone you see,

For otherwise you will behold it not.

To give this gift is how you make it yours.

- A Course in Miracles

I don't know about you, but some days the world can just break my heart.

Yesterday was one of those days when I was reminded of how ridiculously blessed I am, and stunned again by what people endure, how much suffering there is in this world. Where do you find meaning, where do you find love, when life feels bleak, when you are on the streets, when nothing in life has mapped out as you planned? How do you keep going? How do you find grace?

Yesterday I met Joseph, in his 80s, white beard, red face, a jack-o-lantern smile with a handful of crooked teeth and open spaces in-between. Fashionably dressed in a white plastic apron, white paper hat, and clear plastic gloves, I poured red Kool-Aid into Joseph's paper cup at Glide (www.glide.org), where my friend Reema and her mom Nora and I were serving meals Thanksgiving day. Joseph was cheerful and a flirt and promised me that if I liked older men, he'd take good care of me.

As the crowd filed in and filled the long tables, Reema, Nora and I poured Kool-Aid and cleared away empty trays with the remnants of turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, ice cream. We shared Thanksgiving greetings and flirted with the cute kitchen volunteers who were scraping the trays. And we flirted with the men and women at the tables, because who doesn't want to be noticed, appreciated?

Young and old, black, white, Latino, Asian, they poured in, an endless stream of men and women, some weathered and beaten by the street life, some dressed like any professional you might walk by on a busy city street. I am often surprised by just how many look like you and me, or our friends, or our parents. A man in a San Francisco Giants hat and black sweatshirt, salt and pepper hair and mustache, a broad smile, could have been my dad.

Why I am the one privileged to serve, rather than wait in line to eat, why I get to put on a name-tag and a paper hat and plastic gloves and hand out meals, why I am blessed to live in a spacious apartment with hillside views in San Francisco, enjoy a full day of meals and good times with friends versus lining up outside Glide, is a question for which there is no simple answer. Life is a complex equation.

I come from a loving middle class family, have been blessed with an outstanding education and have so many resources and friends - I am SO blessed! - that this need never be a reality for me. I have never truly known need, hunger, desperation. I have cried of course, had my heart broken, had my own moments of darkness when I didn't know what to do or where to turn next. But they always pass.

My refrigerator is full, my apartment is warm, my Blackberry is programmed with names of friends and family who love me. I know I am not alone in the world. Glide provides that sense of family, shelter, community for those who have none, and it is for this reason that I keep returning. Glide brings joy and hope into the lives of those who have lost hope, helps them hold on, rebuild their lives, start again.

Yesterday I met Donnie at the church service at Glide. Tall, handsome despite missing some teeth, wearing his bluetooth headset, and just about bursting with energy, Donnie whispered Glide gossip to me in between dancing to the rousing numbers of the gospel choir and jazz band.

An ex-convict who'd turned his life around, he'd worked at Glide for seven years, rescued from the streets by Reverend Cecil Williams and the Glide family. He knew the inside scoop on everyone and was happy to share the stories with me. Donnie called out to the speakers and the singers on stage: "Preach it! Sing it! Amen!" We got up and danced together, held hands during the prayers. "I was saved by grace," he told me. "I was saved by grace."

Later that day, I handed out meals with my friend Andoni as part of "Operation Turkey Day," organized by a caterer in Marin who prepares 500 turkey meals in biodegradable paper boxes with the help of 40 or so friends, and passes them out on the streets of downtown SF. Every box was hand-decorated in colorful marker with a Thanksgiving message, holiday greeting or positive words: Joy. Yes. A simple red heart. We passed out boxed lunches, juice boxes and clean white socks. In less than 20 minutes, 500 meals had been distributed. So many hungry people.

As an experiment yesterday, I skipped breakfast and lunch just to see what it felt like to be hungry. My stomach churned and I felt a little nauseous, but I knew I had Thanksgiving dinner coming up with friends at 4:30. No real hardship here.

At 2:30 I broke down and ducked into Sears Restaurant on Powell Street to order up a steaming plate of fish and chips, just because I could. I was craving fish, and had my wallet in my pocket, and there was nothing stopping me from ordering a big plate, pouring vinegar on my fried cod, dipping french fries into tartar sauce or ketchup.

The restaurant was about half-full on Thanksgiving day, with couples scattered around eating plates of turkey and all the fixings, most of them in silence. Companionable silence? or lonely silence? I find it striking sometimes how many of us seem alone or lonely even in a room full of people. At most of the tables, with a few happy exceptions, there seemed to be an absence of laughter, of joy. Even with so much, people are lonely.

And here I sat alone dipping my french fries in ketchup and taking in the scene. Perhaps to stave off my own loneliness, I called my family who were gathered for a meal in New Jersey, across the country. I talked to those I love who are far away, as the phone got passed from my mom and dad to brother and sister, Grandmom, aunts and uncles, cousins. They missed me. They love me. They can't wait to see me at Christmastime.

I ate half my meal, boxed the rest, and offered it to the first man I saw sitting on the street. His face and hands were raw from the sun and street living. He was probably younger than me, but missing most of his teeth, ragged, looking bereft. He nearly broke down when I offered him the meal, red eyes shining. "But I'm not allowed to ask women for nothing!" he protested.

I felt the heartache of a man holding onto a promise he had made to someone, words that still held meaning for him, even when he had nothing else left. "But I gave it you," I said. "You didn't ask."

"Thank you ma'am, thank you ma'am, thank you ma'am!" he shouted.

Two hours later I headed to the home of Betty and Ernie, friends of mine in their 80s who are my "adopted grandparents" in SF. I wrote an article about Ernie, a retired sign-maker who hand-crafts carnival games, for a local paper and we became fast friends. They told me to consider them "like family." When I decided to stay in SF for Thanksgiving this year, versus flying home to be with family as I usually do, they invited me to their home to share the holiday meal.

I poured miniature marshmallows on top of the bubbling sweet potatoes for Betty before she popped them and the wheat rolls in the oven. I whisked instant mashed potato mix into a boiling pot of water, milk and butter until it was thick and creamy. Ernie set the table and poured us glasses of white wine.

Four of us ate dinner together - Ernie, Betty, me and their son Bob, who is an alcoholic in his 40s who still lives at home. "I'm an isolationist," he told me. He holes up in a little cluttered room in the back of the house. During dinner, he got up often to refill his beer glass.

"This is the first time I've had dinner with my parents in about two years," he told me, when Ernie and Betty got up to get the pie and clear the plates. "I have nothing to say."

Yet he kept up a steady stream of conversation, as we sat and talked for four and half hours, the whole family, about politics and spiritual practice and the general state of the world. Bob is widely read, but lives in his own world. His body has been ravaged by the alcohol abuse, nose red and pocked, teeth brown, legs skinny in ragged jeans.

He still has dreams. Don't we all have dreams? After dinner, he offered me a shot of tequila from a bottle that he said he'd found on the streets of Mexico years ago. He told me about his dream - to be a war correspondent in Iraq. He'd served in the army years ago and traveled, and felt he'd have a unique perspective to offer. "How do you think I could get there?" he asked.

I told him my journalistic work was much more local, stateside, and that I didn't know the path to get there. What can you say? He drank himself silly, taking a slug directly from the bottle. "I shouldn't be drinking this," he said.

"I guess you don't know much about my profession now," he said. "I work in commodities." He recycles bottles, scavenges on the streets, picks up an occasional odd job - gardening or painting - to buy his bottles of beer. This is his "career."

We all have dreams. We all have stories about ourselves and our lives and how we've ended up where we are, and when it's too hard to face the reality, some turn to booze, or sex, or money, or food, to try to fill the hole inside. We all feel lost sometimes and we all have our own ways of coping.

Some of us are blessed with better coping mechanisms, intact family structures, good work that pays the bills and then some. We have so much, some of us, that we can afford to take fancy vacations to far-off places, buy gifts for our friends and family, take a day at the spa, sit at home and make art.

I am one of these. I go away on yoga retreats. I’m going to Argentina to visit my sister for Christmas. I am privileged beyond belief to be able to sit here in a warm home, keys clicking as I type this, hot cup of tea beside me, a closet full of clothes, shelves full of books, walls hung with art collected from my travels around the world. I do not take any of this for granted.

I have been blessed with joy and abundance in my life, with peace of mind, and I do my best to give that back. Some days I feel like there is so little I can do to make an impact, with so much suffering in the world.

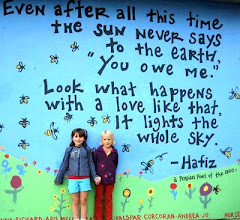

But I do what I can, where I am, with what I have. I shine my light because I feel that it is my duty and responsibility in this world to give back, and it is my joy. I give because it replenishes me. I shine, because I can.

And I choose to focus in my own life on all the JOY - my family, my friends, my writing, my dancing, the beautiful city where I live, all the blessings of every day. What we focus on increases. The Buddha teaches that in this life there will be pain - sickness, old age (if we are lucky enough to live a long life!), death. We can't escape from the reality of life in this body.

And yet, he also teaches that suffering is optional. It is possible to find freedom in our own lives from the suffering created by our own thoughts, and to share that sense of freedom with others. That is my practice and my path, and I do my best to walk it every day.

I send my love to all of you today, who are the true blessings in my life, and ask that we all just remember on this holiday how very blessed we are, and that we reach out with compassion to others in the world who are suffering and broken, when we can. That we shine our light and share our joy, those of us who have so much.

That we do what we can to make others feel less alone in this world.

May you have a blessed holiday season, and always know that you are loved.

Lisa Powell Graham, November 2007