METAMORPHOSIS (How I Became The Butterfly...)

If we had not been in silence, the afternoons long and full and wordless, senses of sight and touch and smell heightened without the web of words weaving through the air to connect us, I might never have noticed the butterflies, wings fluttering ever so slightly on the surface of the water, these butterflies trapped by the weight of their own dampened wings, unable to fly.

They were so elegant, delicate, helpless.

One by one, I plucked them out of the pool, gently holding each one on my fingertips, up to the sun so the wings could dry. One by one, I sat with them for minutes that stretched on like quiet hours, the second hand on the clock above the pool slowly circling around, seconds ticking away while their delicate orange and black wings dried.

I watched them gently moving in my hand, the hind and fore wings stirring, the thorax and proboscis used to sip flower nectar bending with the wind of my hot breath. These creatures were small, complex, miraculous.

After about 10 minutes when the wings were dry and flapping open, I would shake each butterfly off my hand, and scoop another one out of the pool.

They were my personal symbol, a metaphor for my own transformation. The massage therapist who had kneaded my shoulders and back earlier in the silent retreat, trying to free me of my anxiety, told me as she rubbed my shoulder-blades, “I feel four sets of wings growing in.”

Four sets of wings. Which angels were these sprouting wings out of my back, I wondered?

Surely Eric was one, my guardian angel, the man I loved who had died when I was 22. Surely my grandfather, my mother's father whose sky blue eyes and thousand-watt smile I had inherited.

I didn’t know who was responsible for these other sets of wings. Maybe I was turning into an angel myself over time, after all I had suffered and learned.

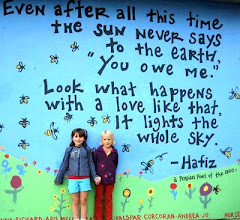

Going on silent retreat was new to me. Here I was, camped out on the cliffs above Santa Barbara, on a ranch once owned by Jane Fonda and where Michael Jackson had donated the money to build a theater.

I was there with 25 other students, devotees of my yoga and meditation instructor Dina, who was teaching me how to love myself again, how to open my heart and soften so that I wouldn’t talk to myself in such mean ways. For such a kind woman, I could be ruthless with myself.

I couldn’t remember ever not being that way, ever since I was a child prodigy and adults fussed over me and told me I would be great at everything. I appreciated the attention, and was terrified by the pressure. How would I save this planet of ours, and keep it spinning on its axis, when wars and poverty threatened to make it implode, our beautiful blue and green sphere crushed by the weight of all the hate in the world?

Fixing the world felt like my job. Well into my 30s, I had never gotten over that, even after earning degrees from Princeton and Harvard, organizing events for Hillary Clinton, working for San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, and being asked to run for mayor of the small city where I’d lived before moving to SF – Troy, New York.

That is why being on retreat for a week in total silence, rising each day at 7 a.m. to meditate, doing yoga for four hours a day, phone turned off, computer at home, nobody calling me or emailing me or counting on me for anything, felt like such a relief.

Here I could just be, simply enjoy the luscious sweetness of every bite of ripe papaya, raspberries, peaches, pineapple, apple, drizzled with yogurt and sweet coconut and raisins, as I spooned it into my mouth in the morning. Here I could just lie in the grass for hours, lazing in the sun like a cat, stretching out to catch the rays, sliding across the grass to a new golden patch of light when I fell into shadow as the sun dipped west.

Sunsets over the cliffs were dazzling, skies striped in pink and purple, the sky dropping away, earth falling straight down in a sheer wall that bottomed out at houses, one mile down, with the city of Santa Barbara in a lit-up grid beneath us, and the ocean beyond that.

The next year when I returned for the same retreat, the scene would be different, the skies filling with smoke and the trees in the distance leaping with orange flames. The wildfires were creeping closer and closer, and we eventually had to be evacuated.

The helicopters swooped in overhead, diving down to scoop up baskets full of water and rushing back to pour it over the flames, creating a hissing cloud of steam over the forest, again and again. I felt like I was in an action adventure movie.

And my life certainly didn’t need any more drama. Nor did I want any more fires.

Before I chose the butterfly as my metaphor, I thought of myself as the phoenix rising from Greek mythology. These birds were identified with the sun and said to have a life span of 500 to 1,000 years. As the end of its life approached, the phoenix would build a nest of myrrh, set it aflame, burn down and in three days rise again.

That had been me. My story was one of renewal and rebirth.

The worst of it happened between ages 20 and 22, while I was in college. Young, naïve, Princeton undergrad, an accidental overachiever who aced every class in high school without trying and now had to put some effort in, I was fumbling my way through college, as any mildly depressed, overweight co-ed feeling out of place at a school full of rich and pretty people might do.

During Christmas break sophomore year, I drove south from my parents’ house in Massachusetts to a friend’s party in Rhode Island. I didn’t want to get drunk, knowing how awful it felt – vertigo, throwing up, passing out. Been there, done that.

I decided to only have two drinks that night. I just wanted to hang out with my friends and relax.

At some point during the night, someone slipped something into my drink, and the rest of the night was erased, except for one slice of memory in which I was lying on my back in the backseat of a car with a man pounding into me and dark glass behind that. The man who raped me left me passed out half-naked in the back of his car.

It was my guardian angel Eric, who I was sure was responsible for at least one of the sprouting sets of wings the massage therapist talked about, who found me in the car, carried me inside, cleaned me up, and put me to bed.

I remember none of this, only that when I woke up in the morning and saw the face of my rapist in the kitchen, bright white countertops glaring in the sun, glasses of orange juice on the counter, and his countenance – I wanted to kill him.

I never filed charges because I thought I would be the one put on trial. I moved on with my life.

I took a year off from Princeton to figure out what to major in, since I’d drifted during my first two years. When I returned to school, I was a jubilant English major, writing poems and reading 19th century Victorian novels, ridiculously happy to bury myself in books again, which had soothed and comforted me as an overly smart, shy child.

During the winter of my senior year, I started dating a local starving artist, a “townie” who lived in Princeton but did not attend the university. Alan was six feet tall with sculpted muscles, a toned and hairless chest as I would soon find out, almond eyes, café au lait skin, a chiseled jaw. He was half-Black and half-White but looked Latino. He was impossibly handsome.

He had been courting me for nearly a year, chatting me up in the student center rotunda café. I had steadfastly ignored him but eventually he roped me in by offering to do a pen-and-ink portrait of my family, modeled after a photograph. I was so touched that he created this piece of art for me that I agreed to go on a date with him.

The first week was okay, consisting of dates at Burger King which he could manage on his budget, a bottle or two of cheap champagne that we drank before stumbling back to my dorm room, and smoking cloves in the student café. By week two, my intuition was flashing red neon signs saying “Run fast!” and I was just as steadfastly ignoring them.

Alan had started to display another side of his personality, which included telling me “jokes” about how he was going to kill me. “That’s not funny, Alan,” I’d say, and he’d always just laugh and shake his head and say, “I’m just kidding baby, take it easy.”

One day in the basement of the dorms while folding his laundry, I discovered a pair of orange pajama bottoms with the word Trenton Psychiatric Hospital printed on them, and Alan’s last name stamped on the waistband. I froze, terrified, told Alan that I needed to get more coins for the dryer, ran back to my dorm room, and locked myself in, heart pounding.

Who was this man? What was his history? What should I do?

Mouth dry, palms wet, I finally talked myself into confronting him. He’d been strumming songs on his guitar while I did his laundry, and he set the instrument down and began to unravel the crazy story. He’d apparently already been arrested for stalking a woman who “couldn’t take a joke” when he’d threatened to kill her, he said. He had kicked out the back window of the police car when they arrested him. He had impersonated a crazy person, he said, going ballistic, so they would put him in the psychiatric ward instead of in the jail overnight. Apparently, it worked.

God only knows why I did not break up with him on the spot, but I didn’t know how to, and felt that maybe this was my fate. I’d been reading tragedies for my English class – Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Isolde. Perhaps I would die young at the hands of my lover. Perhaps that was my path.

That March, as I was struggling to figure out how to leave Alan, who was getting more crazy by the day, I got the phone call that my beloved angel Eric, who I’d known and loved for nine years and who I felt sure I would marry one day long off in the future once I got all my silliness and insecurity out of my system, was back in the hospital for surgery again.

Eric had a condition called Marfan’s Syndrome, a congenital disorder of the connective tissues that had weakened his aorta. He had survived open heart surgery at 19 and took impeccable care of his health, walking every day, taking all the required pills, altering his diet, and even giving up basketball, the sport he most loved.

He was training in college to be a sports photojournalist, so he could document the sport he loved, since he could no longer play.

I could see Eric and myself years into the future, as his family’s lakehouse in Maine, a rolling tumble of children – our children – falling off the couches, laughing, as we loved and laughed and lived, a happy family together. I felt sure that would happen – someday – although in the interim I dodged his attempted kisses, too frightened by the tenderness I felt for him, and too sure that I would hurt him if I did not get my own wildness and confusion out of my system first.

Obviously, he would live a long life, and obviously we would be together someday, if I could only survive Alan’s craziness.

Instead, one Friday in March, while I was up late trying to write another essay about a tragic love story murder-suicide, I found myself playing sad love songs, Mozart’s Requiem and U2’s With or Without You, Eric’s and my favorites, staying up all night. I thought I was going to die that night. I thought Alan would finally break in and snap my neck and it would just be over.

At 7 a.m. I finally collapsed, sleep drugging me and knocking me into bed. Two hours later the phone started ringing, and ringing. I refused to answer it.

Somehow I knew. I didn’t want to know. I didn’t want the truth.

I was alive, and Eric was gone. He’d gone into the hospital for surgery number two, and survived the night at St. Luke’s Hospital in Texas. In the morning at 7 a.m. his heart exploded.

I was inconsolable. This was not supposed to happen. This man was my future, once I got my own life straightened out.

Suddenly my life split in half, into my life with Eric and my life after. He was gone. I was suddenly shocked awake into my own life, fed up with Alan’s craziness, since he had kept stalking me after I finally broke down and had him arrested, and it took five men to pin him down to drag him flailing and shouting out of my dorm room.

I was no longer willing to leave my future to fate. I moved out of state, back into my parents’ house, and spent the first three months back there planning a memorial event for Eric. I withdrew from school for the semester. I couldn’t stand it that he was gone, and that I’d never had the chance to tell him how much I loved him.

Tall, lanky, gangly Eric, the gentle giant, the captain of our high school basketball team when I was a cheerleader, with front teeth crooked from a childhood sledding accident, and the big span of his hands that liked to pat me on the head, Eric with his caramel brown eyes, knowing looks, the way he’d look at me sideways, shaking his head, Eric with his winning smile, was gone.

That summer was a blur. I spent it mostly smoking pot with Eric’s sister Niki in the basement of their mom’s home. I couldn’t deal with life for a few months, but by the fall was ready to go back to school. This time I moved to Boston to live with a junior high friend, taking classes at Harvard and UMass Boston and transferring the credits back to Princeton so I could finish my degree.

I felt him around me all the time. I convinced myself I would be fine. I went to see a therapist now and then, telling her about the rape, that it wasn’t a big deal to me, telling her about Alan, saying I was over it. We talked about Eric and she tried to assuage my guilt that I had never told him how I felt.

Somehow I knew that he knew that I loved him.

One year and three months after Eric died, I graduated from Princeton. It was 1995 and I was 24. I was ready to take the world by storm, get a job at a fancy publishing house in NYC doing editing, and to write my own books.

Until my world started to collapse, the ground crumbling beneath my feet, feeling as if I was sliding off a cliff with no roots or trees or rocks to grab onto. Suddenly I felt into a state of paralysis, unable to perform simple actions in order to move my new career forward. Suddenly, I felt as though I’d screwed everything up and my life was over.

Suddenly, I was in the middle of a nervous breakdown that no one had anticipated, plotting my own death. Would it be by knife, gun, noose, an overdose?

While my family frantically tried to keep me alive, I focused only on my suicide, knowing I had to end it. I snapped. Years later, I read and learned about post-traumatic stress disorder, and with all my poor young body had been through in two years – the rape, the stalking, Eric’s death – then trying to pretend everything was “fine,” it was no wonder that I lost my mind for a while.

At the time, all I knew was that I felt sure I had ruined everything, that my life was over, that I needed to die.

So I took every pill I could find from all the prescriptions the doctors had me on to keep me tethered to reality, and mixed it with anything else I could find – Tylenol, drugs in my mom’s medicine cabinet – swallowing dozens of little white pills in one fell swoop.

When I woke up in a stupor, limbs limp like noodles and so waterlogged that I couldn’t move, trapped in my own body, I knew I was still alive. “Okay, God,” I said, “I guess you still want me alive. If there is a purpose for my life, I really wish you’d show me what it is!”

The next fifteen years of my life would become a frantic search for just that. Why was I here? What was I supposed to do with this life of mine?

Obviously I was still alive, and obviously the world still needed saving.

I tried on so many hats – should I go to divinity school to pay homage to the God who had saved me from myself? Should I be a “real” writer, which was what my heart longed to do? Should I work in marketing, which is what seemed more practical? Should I run for office, which is what people in my town started recruiting me to do after I morphed into a neighborhood leader somehow…. What exactly was I supposed to do with this one life?

The years flew by in a flurry of activity and an outward display of happiness, despite the fact that I would spend nights in a panic, locked in my bathroom, a cell phone in one hand and a knife in the other, still convinced that someone was going to break in and kill me. I got really good at hiding my terror and anxiety. It was my little secret.

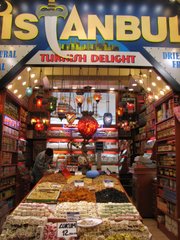

Somewhere along the way, I got married, became a dance instructor, metamorphasized into an accidental community leader, traveled across several continents. I kept achieving, accumulating possessions, striving to be the good wife, citizen, daughter.

I pretended that I had no dark past, only happiness.

And yet the soul is wiser than that, and if it needs healing, sometimes the surface will start to crack. Things fell apart. My marriage ended. My job with the mayor of San Francisco ended. My sublet at my apartment was up. I was living in San Francisco with no income and no job.

Miraculously, things re-aligned for me quickly. A graduate school friend of mine asked me to move into her palatial Pacific Heights home, for free, until I could get back on my feet. I bumped into two Harvard-educated landscape architects while sipping tea at a picnic table by Crissy Fields. They spotted my Harvard baseball cap, found out I was trained in strategic planning, and promptly hired me.

My teachers started finding me – yoga instructors, meditation teachers, wisdom teachers. I was too stubborn to seek treatment for PTSD, and so the universe kept throwing healers at me. One by one they introduced me to new techniques to help me calm my nerves and feel more at peace.

Suddenly this formerly overly agitated and restless overachiever was sitting still for minutes at a time, meditating. Suddenly I was upside down in downward facing dog, practicing in a lineage that spanned thousands of years.

Suddenly I was finding some semblance of peace.

Fast forward five years. It was 2010 and I was living in upstate New York, where I had moved to put my house back together. My ex-husband and I were about to sell our house as the final piece of our divorce settlement when our tenants accidentally set it on fire.

It was around this time that I decided that my symbol should not be the phoenix rising anymore, that the universe was obviously taking my metaphors way too seriously, and that I would become the butterfly instead, emerging from the chrysalis to become a creature of flight and exquisite beauty.

After spending a year rebuilding my house, I started focusing again on building out my career. I really wanted to write books, although I was terrified of tackling this lifelong dream of mine. I also wanted to find someone to love.

I was more peaceful than I had been years earlier, having cultivated a daily meditation practice, with fewer sleepness nights due to the panic attacks, less consistently agitated. My stomach did not churn all the time with worry – just occasionally.

I had steady consulting work and even took the brave step, for me, of telling my story for the first time. I was the keynote speaker at the Take Back the Night rally for victims of sexual trauma. It was utterly terrifying and also liberating. I had spoken the truth out loud, and nothing happened. My friends were still my friends. My career did not fall apart. No one ran away screaming accusing me of mental illness, the prospect of which had terrified me since my breakdown years ago.

I was still just me, living my life, and I finally decided that it was time to write my story as well, to show others that they could recover from something so painful and build a happy life.

Life in general was good from the outside. Yet I still often felt like the chrysalis, wrapped in my cocoon, still hibernating with episodes of mild depression sometimes, still wondering why things wouldn’t align in my love life.

One day, I decided that I’d had enough of my own suffering and drama. I really wanted just to live my happy live, make my dreams come true, and not to stew in the memories of what had happened to me, or what could have been. Something broke inside me again. I just wanted to live.

I sat down and wrote a pledge to myself that I would absolutely live all of my dreams. I wouldn’t let fear stop me. I wouldn’t let my past or my stories about any limitations I imagined I had stop me. I would write my book. I would meet my soul mate. I would raise a family. I would be peaceful and happy.

I signed it, tucked it into a drawer in my desk, and forgot about it.

Suddenly those four sets of wings sprouted. Suddenly I was taking off and not even knowing how. Everything in my life turned around. I found a spiritual teacher who embodied all that I had ever wanted to learn, fervently made a wish to meet him, and much to my shock and surprise found myself spending most of the month of August with him. He was teaching his first workshops in the US, although his home base was India, and I organized them for him. He taught in my town, and stayed in my house.

Suddenly my career dreams started to click into place and take shape. I was nearly 300 pages into my book, which told my redemption story. People who read my weekly blog, which talks about living my dreams, asked to hire me as their life coach.

Suddenly I met the first man I have really liked in a very long time, and thought to myself, I think I just met my husband.

Suddenly everything I’d ever dreamed of seemed to be coming true. And suddenly, it didn’t even matter whether it all materialized or not, because I was profoundly and deeply aware in every cell of my body, suddenly, that every day I have on this planet is a gift.

I tried to end my life all those years ago. Alan wanted to kill me. I was given another chance.

Feeling like a miracle, I have been walking through the days of my life glowing, shining with happiness, so that the people around me want me to drink it in, want me to be the genie in their lamp, want some of my illumination to rub off on them. Suddenly I am so peaceful that I have forgotten how to worry.

Suddenly I realize that I am the butterfly, that my wings are dry, that I can fly into the sunshine over the cliffs, be who I want to be, and that my past is now over.

Suddenly I am simply, beautifully me.

© Lisa Powell, September 2010